For decades, the arrival of a genuinely intelligent machine has been the defining anxiety of the modern workforce. From the assembly-line robots of the 1980s to the algorithmic trading desks of the 2000s, each new wave of automation arrived with a familiar warning: the machines are coming for your job. And yet, employment has persisted — even flourished — through every prior technological disruption. Today, artificial intelligence represents something categorically different from its predecessors, and the question is no longer whether AI will change the nature of work. It already has. The real question is how deep that change goes, and whether the industry professionals building, deploying, and managing these systems are prepared for what comes next.

The short answer, based on the trajectory of AI adoption across enterprise technology, is that the transformation will be profound, uneven, and far more nuanced than either utopian or dystopian narratives suggest. AI is not a single tool. It is a general-purpose technology — analogous to electricity or the internet — whose effects compound across industries, job categories, and organizational structures in ways that are difficult to predict and even harder to measure in real time.

The Cognitive Layer Has Arrived

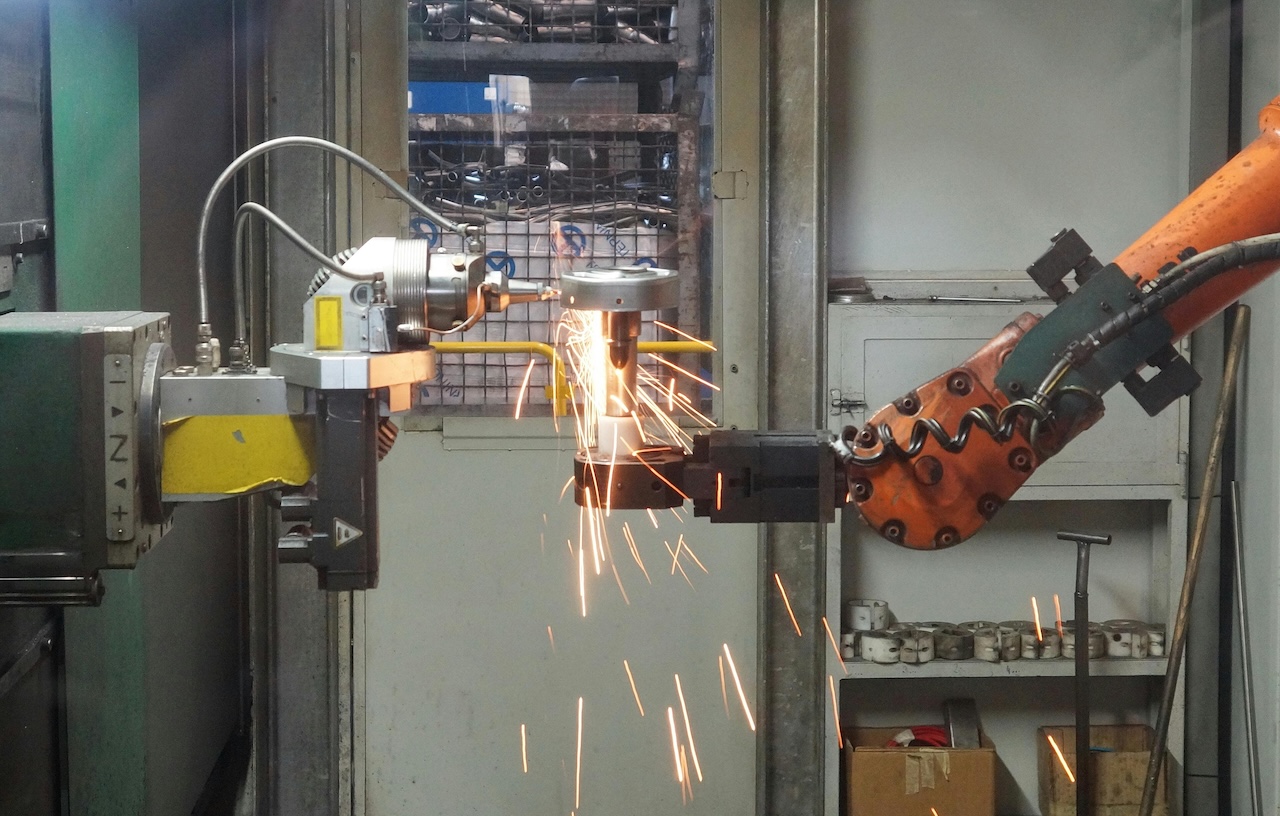

What distinguishes contemporary AI — and large language models in particular — from earlier forms of automation is the domain in which it operates. Previous waves of automation excelled at physical repetition and narrow, rule-based computation. The machines that replaced factory workers performed specific, predictable motor tasks. The algorithms that transformed financial services executed well-defined logical operations faster and more reliably than humans.

Modern AI systems operate on a different layer entirely: the cognitive layer. They draft code, synthesize research, generate marketing copy, parse legal documents, write diagnostic summaries, and engage customers in nuanced natural language conversations. These are tasks that, until very recently, required human judgment, creativity, and contextual awareness. The cognitive layer is where knowledge workers — software engineers, analysts, writers, consultants, lawyers, and medical professionals — have historically been most insulated from automation pressure. That insulation is eroding.

This does not mean wholesale displacement is imminent or inevitable. What it does mean is that the structure of cognitive work is being fundamentally renegotiated. Tasks once bundled together into a single role are being disaggregated. A software engineer who once spent 40 percent of their time writing boilerplate code can now delegate much of that to an AI coding assistant, freeing cognitive bandwidth for architecture decisions, debugging, and cross-functional collaboration. The job has not disappeared — but it has changed shape.

Productivity Gains Are Real, but Distribution Is Uneven

The productivity evidence for AI in professional environments is now substantial enough to move beyond anecdote. Multiple large-scale studies from academic and enterprise research environments have found measurable output gains when knowledge workers are given access to AI tools — particularly in software development, customer support, and document-intensive workflows. One widely cited study of software developers found that those with access to an AI code-completion tool completed assigned tasks significantly faster than those without, with the greatest gains accruing to less experienced developers.

This finding contains an important signal that is frequently underreported: AI’s productivity dividend is not uniformly distributed. In many documented cases, AI tools compress the performance gap between junior and senior workers by giving novices access to capabilities that previously took years of experience to develop. For senior professionals, the gains are often more modest in raw output terms but meaningful in terms of scope — AI allows experts to take on broader problem sets, supervise more work streams, and operate at higher levels of abstraction.

For technology organizations, this creates a genuine strategic inflection point. The talent calculus that has governed hiring decisions for a generation — the premium on deep specialization and years of accumulated experience — is being complicated by tools that can partially replicate the outputs of that experience. This does not make expertise obsolete. Domain knowledge, systems thinking, ethical judgment, and the ability to identify when an AI output is subtly wrong remain irreplaceably human capacities. But it does mean that the definition of a productive professional is being rewritten in real time.

The Emerging Architecture of Human-AI Collaboration

The organizations making the most effective use of AI are not simply deploying it as a cost-reduction tool. They are redesigning workflows from first principles around the complementary strengths of human and machine cognition. This means being precise about what AI does well — speed, pattern recognition, synthesis at scale, tireless consistency — and what it does poorly: judgment under genuine uncertainty, ethical reasoning, stakeholder relationship management, and the ability to ask the right question rather than merely answer the one posed.

In software engineering, this has produced a new operational model that some practitioners are calling ‘AI-augmented development.’ Engineers work alongside AI coding assistants not as passive consumers of auto-generated code, but as active editors and supervisors — reviewing AI output for correctness, security vulnerabilities, and alignment with broader system architecture. The cognitive demand on the human has arguably increased, not decreased: the engineer must now maintain a critical meta-awareness of both the problem domain and the AI’s tendencies and failure modes.

Similar dynamics are playing out in data science and analytics. AI can now perform exploratory data analysis, generate visualizations, and even surface preliminary hypotheses from unstructured datasets at a pace no human analyst can match. But the interpretation of those findings — understanding causality, communicating uncertainty to non-technical stakeholders, and connecting statistical outputs to business decisions — remains firmly in human territory. The analyst’s value proposition has shifted from data manipulation toward data translation and strategic framing.

The Skills Premium Is Shifting

If there is one near-universal implication of widespread AI adoption for technology professionals, it is this: the skills premium is shifting away from execution and toward orchestration. The ability to do a well-defined task quickly and accurately — write a SQL query, generate a data visualization, draft a project specification — is becoming less differentiating as AI tools democratize access to those capabilities. The premium is moving toward the skills required to direct, evaluate, and integrate AI output into coherent systems and decisions.

This includes what researchers sometimes call ‘prompt engineering’ in a narrow sense, but the more important capacity is broader: the ability to decompose complex problems into components that can be delegated to AI versus those that require human judgment, and then to synthesize the results into coherent outputs. It is, in essence, a new form of project management applied at the task level — and it requires a clear-eyed understanding of what AI can and cannot do reliably.

There is also a growing premium on what might be called ‘AI skepticism’ — the professional capacity to critically evaluate AI-generated outputs rather than accepting them uncritically. As AI systems become more fluent and confident in their outputs, the failure modes become harder to detect. An AI assistant that writes plausible-sounding but factually incorrect code, or that produces a convincing but subtly biased analysis, represents a professional liability that falls on the human who signed off on the work. The ability to audit AI output is rapidly becoming a core professional competency.

Organizational Risk: Speed Versus Governance

For technology leaders, the strategic challenge is not simply adopting AI tools — it is doing so in a way that captures productivity benefits without creating new organizational risks. The most significant risk is not the one that dominates public debate (existential AI displacement) but a more prosaic and immediate one: the systematic propagation of AI errors through workflows that lack adequate human review checkpoints.

The speed at which AI can generate outputs — code, analyses, communications, documentation — creates organizational pressure to reduce review cycles. That pressure can be appropriate when AI is handling low-stakes, easily audited tasks. It becomes dangerous when AI outputs feed into high-stakes decisions — security-critical code, regulated financial analyses, medical summaries — without sufficient expert review. The governance architecture for AI-integrated workflows is still being built, and most organizations are significantly behind the pace of their own AI adoption.

This is one area where the technology industry’s instinct to move fast and iterate creates genuine risk. The organizations that will manage AI adoption most successfully are likely those that build review and audit mechanisms into AI-assisted workflows from the outset, rather than retrofitting governance after problems emerge. This requires investment in human expertise — reviewers, auditors, domain specialists — at precisely the moment when AI-driven efficiency gains are creating pressure to reduce headcount.

The Longer Arc: Adaptation, Not Extinction

Viewed through the long lens of economic history, the concern that AI will simply eliminate the jobs it automates is almost certainly too simple. The more plausible trajectory — consistent with the historical pattern of general-purpose technology adoption — is a period of significant labor market disruption and skills transition, followed by the emergence of new job categories and economic activities that are difficult to anticipate in advance.

The internet eliminated typesetting, travel agency, and classified advertising as major industries. It also created cloud infrastructure engineering, digital marketing, UX design, and the entire creator economy — none of which existed in their current form before the mid-1990s. AI will almost certainly follow a similar pattern: contracting some categories of cognitive work while expanding others that leverage distinctly human capacities or that involve directing and improving AI systems themselves.

What is different this time — and what makes AI more challenging to navigate than prior general-purpose technologies — is the speed of the transition and the breadth of cognitive domains it touches simultaneously. The internet disruption, massive as it was, primarily affected industries built around information intermediation. AI’s reach extends to any domain involving language, reasoning, or pattern recognition — which is to say, most of the cognitive work economy.

What This Means for Technology Professionals

For practitioners working at the intersection of AI and enterprise technology, the practical implications distill to a few clear imperatives. First, treat AI literacy as a professional obligation rather than an optional skill. Understanding how large language models work, where they fail, and how to evaluate their outputs is becoming as foundational as understanding version control or database normalization.

Second, invest deliberately in the skills that AI complements rather than replaces: systems thinking, cross-functional communication, ethical judgment, and the ability to ask better questions. These are the capacities that are becoming more valuable, not less, in an AI-augmented environment.

Third, engage seriously with the governance dimension of AI adoption in your organization. The professionals who build the frameworks, review processes, and institutional knowledge for responsible AI deployment will be defining figures in this transition — not passive recipients of it.

The machines are, in fact, changing work. But the nature and pace of that change is being shaped, right now, by the professionals who are building, deploying, and governing these systems. That is not a passive role. It is an opportunity to help write the next chapter of how humans and intelligent machines work together — and to ensure it is written thoughtfully.